Suburbia and the Bicycle

This is an article I wrote for BikeHouston. Although most posts on my blog are not proofread or edited, this one is in special need of review.

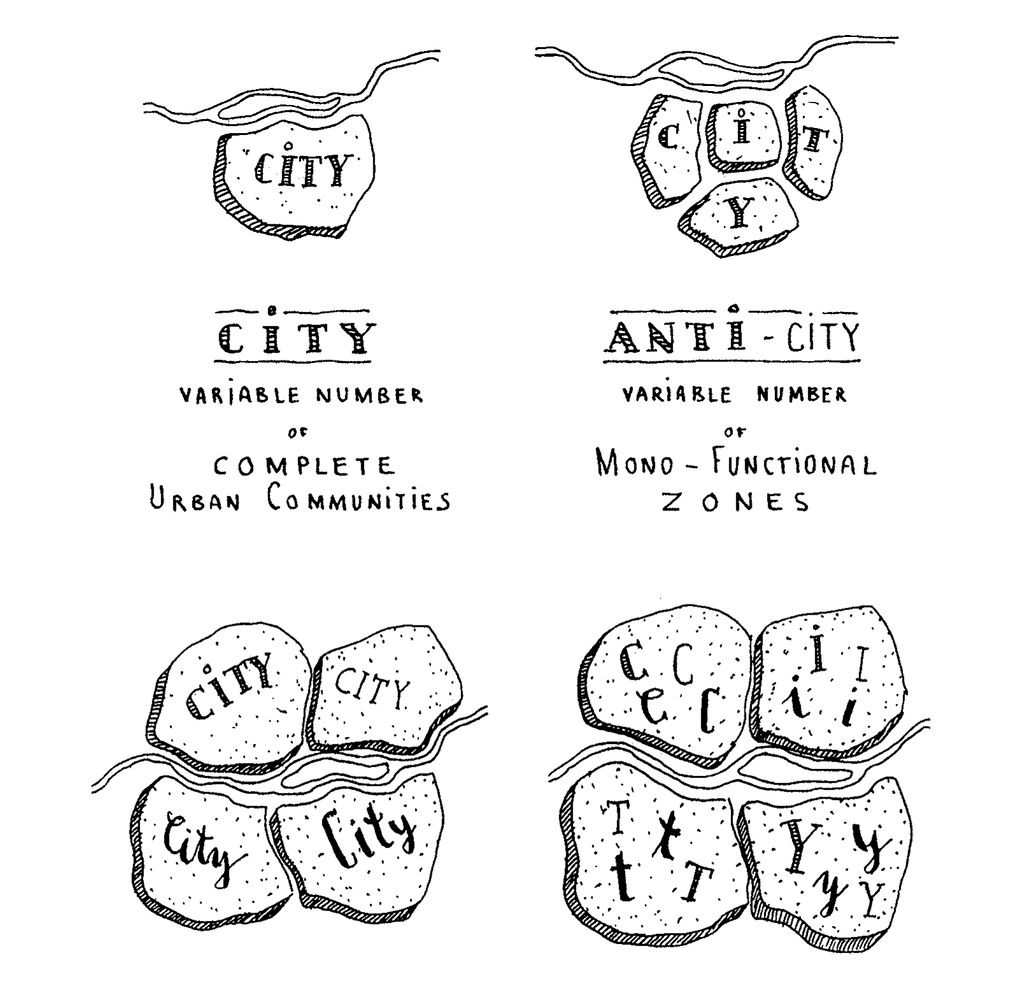

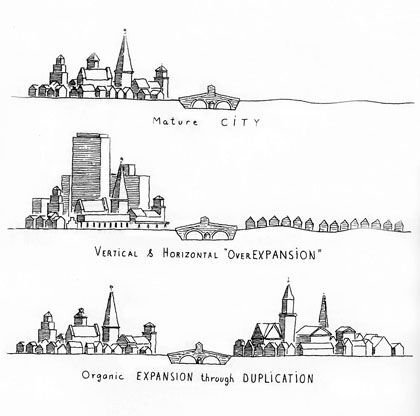

Illustrations by Leon Krier from his book Drawing for Architecture

Modern business is conducted with amazingly intricate supply chains spanning the world. It is a finely tuned, yet delicate, machine that produces products ranging from integrated circuits to pharmaceutical drugs at incredibly low prices. As Adam Smith’s fundamental tenet of economics goes “as the size of the market increases so does division of labor and thereby productivity”. Supply chains have become so complex that it took Intel seven years to figure out how to stop their supply chain from inadvertently supporting conflict areas like the DRC – SEVEN YEARS for a company to figure out its own supply chain. Of course, this is to be expected: the market aggregates information that no one person has access to that is part of the reason why we all have computers in our pockets. We all benefit from from economies of scale – when the production of an iPhone spans the world and involves millions of people it becomes inexpensive.

Division of labor, which has proven so successful in economics, should not be literally applied to urban design. Many North American cities are built in an interesting fashion: a central business district, surrounded by a planned residential area so that everyone may have their own house, yard, and access to cheap consumer goods. Instead of having multiple neighborhoods that each have their own small grocery store, and other small businesses – cities began having Costco, TJ Maxx, and McDonalds that served multiple communities. These are great businesses! I can buy a hamburger for a couple bucks – that’s a great thing. But are there costs to bringing division of labor into the design of cities? You bet there is. Just because the division of labor works wonders for global markets does not mean it work well for cities or neighborhoods.

Human beings thrive in small communities. That is, there is some evidence that humans cannot have personal, and close relationships with over 100 people (the famous Dunbar number). Clearly human communities have different scales:

-

family

-

friends

-

neighborhood

-

city

-

state

-

nation

-

world

Human communities are fractal-like – as you zoom out you see similar-yet-different patterns. The problem with the large top-down cities across America is that they often skip over the neighborhood stage. Old European cities are collections of neighborhoods, that is, they are micro-cities where the needs of the locals are satisfied in their local jurisdiction. They are redundant, meaning that each neighborhood has components necessary for life. But the neighborhoods are unique, because they were not designed for and by the same sorts of people – every neighborhood is used in a fundamentally different AND similar way. This also means that the shops are less efficient than one mega-store that can service a huge segment of a geographically spread-out population. But the benefits of redundancy are numerous.

Many Americans think the suburban lifestyle is the antidote to the coronavirus: after all, suburbia consists of spread out houses on individual blocks of land, often times without the benefit of a sidewalk. But eventually, most Americans need to leave the house, for food, work, or other errands. There is even evidence that repeated congregation of people from geographically disparate areas in the same space (like a grocery store) leads to much higher rates of infection. Charles Marohn from Strong Towns explains:

The suburban experiment includes a false sense of security of allowing people to isolate in a pod of residential dwellings. That is, isolated until they need to go get food. Or go to work. Or, as was apparently happening in my hometown this weekend, when half the population of Central Minnesota needs to get out and buy mulch at Home Depot. It is at this point that everyone in the entire region congregates in one of the efficient pods we’ve set up for commercial transactions. For spread of a virus, there is no better petri dish than the frequent mass clustering of people demanded by the Suburban Experiment.

Marohn makes the argument that coronavirus heralds the end of the traditional urban/suburban/rural split in urban geography. That instead of having business districts that slowly turn into spread out housing there would be a redundant, decentralized, or fractal pattern of neighborhoods. Instead of waiting in a huge line at Costco for toilet paper, you could go down to your local grocer and buy toilet paper there. The neighborhood would act as a cell in a larger social body – if the neighborhood got sick, the larger social body (the city) would easily be able to isolate it (since it is self-reliant and self-contained)). In his article, Marohn uses this drawing by Leon Krier to show three types of urban development patterns.

Krier’s other illustration at the top of this article illustrates the same idea: when neighborhoods become mono-functional (not self-sustaining and not redundant) cities are no longer communities of people, but business districts. This is division of labor run amok, human beings do not like when their environments are shaped like global supply chains. Humans like cities that respect their various social networks: a place for family, a place for friends, a place for neighborhoods, etc. This also has massive economic benefits: cities that are designed for people attract and maintain healthy human workers – healthy cities are productive cities. Economic prosperity is dependent on division of labor, but it’s also dependent on the quality of life of human capital. Humans who live in wholesome communities will enrich not only their communities, but also the world. We can still have our potato chips! But cities should not be designed like the supply chain that brings potato chips to your grocery store.

How does the bicycle fit into all of this? The bicycle is an amazing tool at the level of urban communities – the bicycle is not a tool for mono-functional zones. Biking across distended highway cities is harrowing and incredibly dangerous. Houston has highways and inhuman decaying neighborhoods, but it also has thriving and active communities. There is hope that by building communities, even within an organism as sprawling as Houston, we can make bicycling viable for everyone.

Our aim at BikeHouston is to foster healthy and dynamic cities by creating human-scale transportation infrastructure in, and between, communities. It is through a combination of both urban design and urban transportation that we can make our city beautiful, safe, and economically productive for all Houstonians.